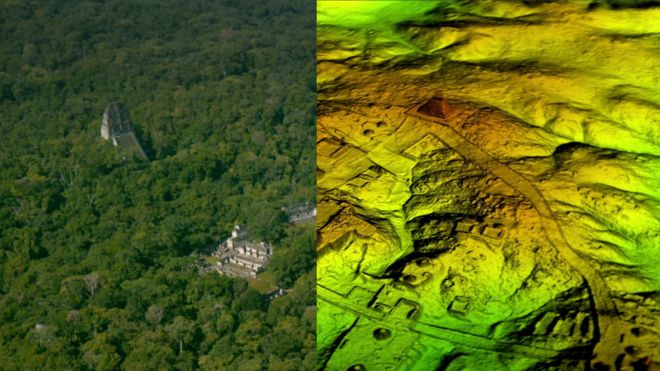

Researchers have found more than 60,000 hidden Maya ruins in Guatemala in a major archaeological breakthrough.

Laser technology was used to survey digitally beneath the forest canopy, revealing houses, palaces, elevated highways, and defensive fortifications.

The landscape, near already-known Maya cities, is thought to have been home to millions more people than other research had previously suggested.

The researchers mapped over 810 square miles (2,100 sq km) in northern Peten.

Archaeologists believe the cutting-edge technology will change the way the world will see the Maya civilisation.

“I think this is one of the greatest advances in over 150 years of Maya archaeology,” said Stephen Houston, Professor of Archaeology and Anthropology at Brown University.

Results from the research using Lidar technology, which is short for “light detection and ranging”, suggest that Central America supported an advanced civilisation more akin to sophisticated cultures like ancient Greece or China.

“Everything is turned on its head,” Ithaca College archaeologist Thomas Garrison told the BBC.

He believes the scale and population density has been “grossly underestimated and could in fact be three or four times greater than previously thought”.

How does Lidar work?

Described as “magic” by some archaeologists, Lidar unveils archaeological finds almost invisible to the naked eye, especially in the tropics.

- It is a sophisticated remote sensing technology that uses laser light to densely sample the surface of the earth

- Millions of laser pulses every four seconds are beamed at the ground from a plane or helicopter

- The wavelengths are measured as they bounce back, which is not unlike how bats use sonar to hunt

- The highly accurate measurements are then used to produce a detailed three-dimensional image of the ground surface topography

Revolutionary treasure map

The group of scholars who worked on this project used Lidar to digitally remove the dense tree canopy to create a 3D map of what is really under the surface of the now-uninhabited Guatemalan rainforest.

Archaeologists excavating a Maya site called El Zotz in northern Guatemala, painstakingly mapped the landscape for years. But the Lidar survey revealed kilometres of fortification wall that the team had never noticed before.

“Maybe, eventually, we would have gotten to this hilltop where this fortress is, but I was within about 150 feet of it in 2010 and didn’t see anything,” Mr Garrison told Live Science.

While Lidar imagery has saved archaeologists years of on-the-ground searching, the BBC was told that it also presents a problem.

“The tricky thing about Lidar is that it gives us an image of 3,000 years of Mayan civilisation in the area, compressed,” explained Mr Garrison, who is part of a consortium of archaeologists involved in the recent survey.

“It’s a great problem to have though, because it gives us new challenges as we learn more about the Maya.”

In recent years Lidar technology has also been used to reveal previously hidden cities near the iconic ancient temple of Angkor Wat in Cambodia.